Introduction

Begging the Question (Petitio principii): “Begging-the-question fallacy consists of circular reasoning, where the arguer takes for granted the truth of what they are trying to prove”

– Circular Reasoning and The Art of Argumentation

I first started to write this series in September 2023 when I pondered on the connection between Fine Art Nudes, History and Philosophy. Subsequently, through studying the Art of Argumentation and identifying fallacies at play in perception of the nude form, I challenged myself to draw attention to the historical evolution of authentic and idealized beauty standards, while addressing the fallacies in the context of the nude form.

The fallacy of “begging the question” involves assuming the truth of the conclusion in the premise of an argument. In the context of fine art nudes, this could occur if someone assumes that depicting the human body in a particular way is inherently valuable or authentic without providing substantial reasoning.

Great Masters – A Peak back at the Past

The Dance is one of two paintings, it’s companion is called “Music”. In both works, the fives figures are undressed, their genders are unclear, there is lack of detail, and bold colours are used, this emphasizing the art direction of Fauvism and Primitivism. By only using three colours; blue, green and red, with no landscapes or architecture, this life-sized artwork envelopes the viewer. Even though Matisse used an enormous canvas, he carefully used his canvas space to create movement and expression. The position in which the figures are placed are quite important in these paintings, creating a sense of three-dimension whilst connecting the different elements. Is it possible that such simple techniques have been forsaken in the name beauty?

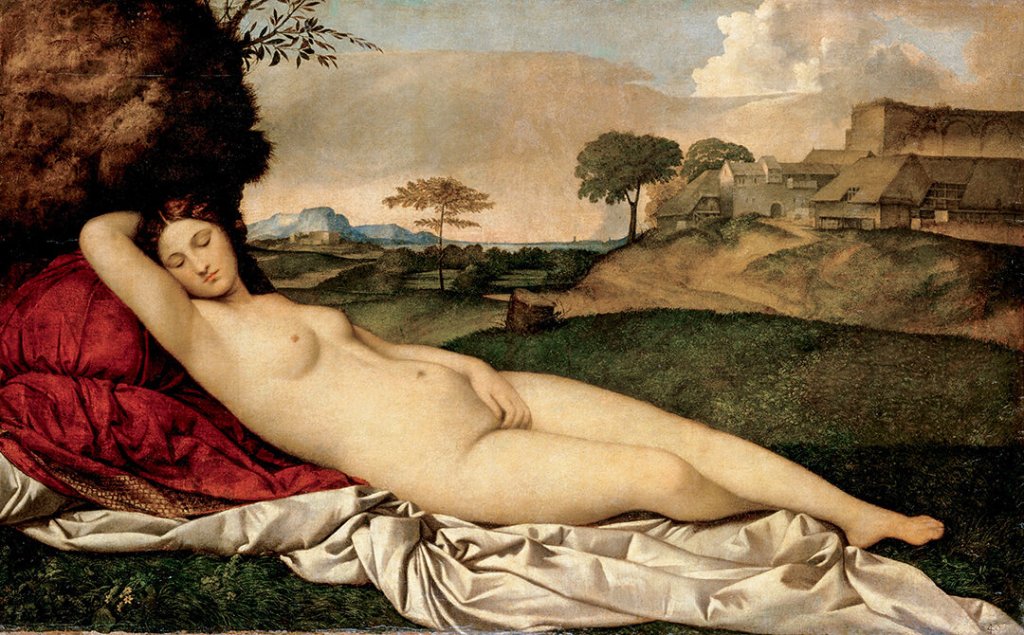

A few periods earlier, we gaze at the work of Giorgione, who painted Venus (The Dresden Venus). Interestingly he never finished this particular painting, it was later finished by his admired and friend, Titian. Inevitably, this sparked debate on how much Giorgione should be credited for the artwork. Amusingly, this could be seen as a beautiful story of collaboration after death. The Sleeping Venus depicts a reclined nude female lying on sheets and resting on a large pillow. This also life-sized artwork was an unconventional and audacious leap for Giorgione’s time, in ways cutting edge. The large landscapes compliment the Goddesses body, additionally the colours help seamlessly blend her nude form with the natural elements of her surrounding. Her right hand gently covers her crotch, her eyes are closed and head gently resting on her left bicep, leaving the viewer reflecting with a profound sense of relaxation. Giorgione was dedicated to painting the nude in it’s most natural portrayal and shape. Using shapes, colours and blending of techniques he captures the natural female form in a stunning, yet erotic display. This depiction of Venus is widely considered to be the most perfect rendering of the Goddess, even to this day. In the case of Giorgione, one could beg the question by presuming that contemporary perspectives inherently surpass the artistic audacity of his era. One should also further consider historical and cultural context that shaped such innovative approaches.

Pre-Modern Influencers

Lucian Freud’s approach to the nude form was to scrutinise, rather than sexualise. A personal favourite of mine. He had a realistic approach to every sheen, freckle and furrow on the body. In the example below, Longman’s skin emerges in an array of hues – mauves, venous blues, ochres, and Cremnitz white – Taut lines can clearly be seen on her neck and clavicle, her lips are almost naturally pulled down by gravity, unlike a modern picture pout. Certainly in his era, and based on Freuds previous work, this was a more comfortable public appeal than earlier reclined female nude paintings. Could it be dubious to assume that his meticulous approach was more effective than modern portrayals of the nude form? Freud once said he wanted his paint not so much to represent flesh as to be flesh; Could we also hold this expectation for our current depictions of the human body?

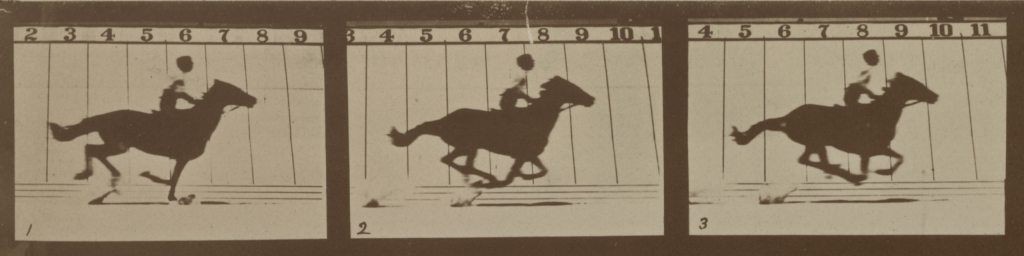

Another lover of the nude, and rather intriguing example – Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge started his career by taking pictures in the Yosemite mountains, lugging around his bulky camera capturing daring photos few would ever think of. Through his early photographic techniques, Muybridge became a popular figure and was later commissioned to capture the movement of a running horse. This was a first of its kind and the earliest example of a modern GIF. Muybridge’s foray into optical gadgets birthed the zoopraxiscope, a precursor to modern projection. Muybridge was able to capture and reanimate his still images using his techniques, a truly remarkable concept of his time. In 1875 Muybridge was accused and tried for murdering his wife’s lover, yet, he skilfully avoided death with the help his lawyer, family and friends. He would live free to produce numerous instances of studies involving individuals in the nude and objects in motion. He was an unconventional, temperamental and eccentric artist far beyond his time, seeking out the intricacies of the body combining the study of motion and anatomy. One might inadvertently beg the question by assuming that his analytical approach to capturing movement surpassed modern interpretations of the nude.

Evolving Perspectives

Matisse, Freud, Giorgione and Muybridge all had shared a profound affinity for innovation and the exploration of the human body, especially the nude form. However, with the rise of the 20th century, printing and photography advancements presented artist with a plethora of new ways to manipulate their images. The supermodel era – 1980s and 1990s, epitomized by figures like Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, and Claudia Schiffer, often depicted models in polished and enhanced photos, presenting a near-flawless aesthetic ideal, one could even say, unnatural. More on that in Part 3.

As we dive into the world of beauty and the depiction of the human form, we’re confronted with an intriguing paradox – are we inadvertently falling into the trap of circular reasoning? In this first part, we explored the historical evolution of authentic and idealized beauty standards, all while coming face to face with the concept of begging the question. But what does that really mean? It’s like assuming something is true and then using it to prove itself. As we took a closer look at artistic masterpieces, from Matisse’s “The Dance” to Giorgione’s “Sleeping Venus,” we discovered deep cultural perspectives in combination with an abundance of techniques used to depict the nude form. Then we encountered Lucian Freud’s unfiltered scrutiny of the human body and Eadweard Muybridge’s innovative capture of movement, both revealing the multifaceted nature of beauty. I now find myself wondering: Does our contemporary lens truly outshine these historical geniuses’ unique insights?

The narrative of reshaping beauty standards will continue as technology advances and industry trends evolve, leading us to question whether we’ve inadvertently abandoned the pioneering spirit of visionary artists. Notably in today’s society, we’re influenced by various pressures, and sometimes fall into the trap of simplifying diverse body types despite our progress in embracing body positivity. So, here we stand at a crossroads, recognizing a need to reconnect with the authenticity of the nude form. By understanding the lessons from the past, including the dangers of oversimplification, we have the opportunity to foster inclusivity, realism, and ultimately pave the way for a more content society

As we continue our journey, Part 2 will unveil more layers of this fascinating exploration. Stay tuned for a deeper dive into the evolution of our perception of beauty and authenticity!

Leave a comment