Appreal To Tradition (argumentum ad antiquitatem): “Using historical preferences of the people (tradition), either in general or as specific as the historical preferences of a single individual, as evidence that the historical preference is correct. Traditions are often passed from generation to generation with no other explanation besides, “this is the way it has always been done”—which is not a reason, it is an absence of a reason.”

– loggicallyfallacious.com

In Part one I deconstructed the Authenticity of Nudes, based on the idea that the fallacy of Begging the Question was at play and we discussed briefly how views on the nude form had evolved to encompass a broader range of interpretation – this can indeed be seen as a transformation in societal norms and values. This transformation challenges the appeal to tradition fallacy by highlighting that beauty ideals and artistic representations are not static but subject to change over time. This leaves the debate open to suggest that there could be more than two or more fallacies at play when discussing deeper meanings behind authentic nudes.

Thus in Part two I will look at it through appeal to tradition fallacy, which occurs when an argument is justified solely on the basis of its historical precedent. In the context of beauty discussions, this can involve advocating for certain beauty standards solely because they have been upheld for a long time, without considering the validity or relevance of those standards in today’s diverse society.

It’s important to note that one can not the use the past as a basis for justifying certain beauty standards. Recognizing that societal norms are not fixed and that they can evolve, allowing for a more open and inclusive discourse that takes into account the diverse perspectives and values of different eras.

The great masters ground-breaking approaches to portraying the human body have contributed to shifting perceptions and opening up discussions about beauty, authenticity, and representation.

Let’s take a deeper look at a few artist that might have influenced perceptions using unique techniques, angles, colours, and my favourite, the use of Chiaroscuro. I might add, viewer discretion is advised as some of this work has been deemed erotic or pornographic. This very controversy underscores my point: the boundaries between art, eroticism, and societal values are fluid, continually shaped by the context in which they are viewed.

Reference Egon Schiele

Upon liberating himself from the confines of academic conventions, Egon Schiele embarked on a profound exploration of the human form and sexuality. His already audacious work took a bold leap, whilst incorporating Gustav Klimt’s decorative eroticism, he ventured into what some might term as figurative distortions – characterized by elongations, deformities, and a candid openness about sexuality. Schiele’s self-portraits breathed new life into both genres, offering a unique fusion of emotional and sexual candor, utilizing figural distortion as a departure from conventional ideals of beauty. In addition to these, he paid homage to Van Gogh’s iconic “Sunflowers,” and delved into the realms of landscapes and still life.

Around 1910, Schiele delved into the realm of nudes, swiftly establishing a definitive style characterized by bony, pallid figures, often imbued with potent sexual undertones. Dejectedly, Schiele also turned his gaze towards children, and was arrested for seducing a young girl of 13. Many of his drawings which were considered pornographic was confiscated by police.

His self-portrait, “Kneeling Nude with Raised Hands” (1910), stands as a pinnacle of 20th-century nude artistry, pushing boundaries and prompting both scholars and progressives to confront their preconceived notions. This unorthodox piece, with its contorted lines and bold display of figurative expression, stirred a sexual uproar, leaving many of its contemporaries unsettled by its explicitness.

In the eyes of Kallir and esteemed scholar Gerald Izenberg, Schiele’s sexuality and gender identity are viewed as fluid and complex. Kallir astutely notes that Schiele grappled with his own sexual and gender inclinations within a historical context marked by shifting gender expectations, the early women’s movement, and the contentious criminalization of homosexuality. In the 21st century, some critics interpret Schiele’s work through a queer lens, recognizing the nuanced interplay of sexuality and identity in his artistry. The unique contours, angles, and colors that permeate his oeuvre continue to captivate audiences, inviting contemplation and reflection on the complexities of the human form. Could one argue that even though Schiele was influenced by his mentors and broader Expressionist movement, his work feels consciously crafted to be different, rather than habitually rooted?

Reference to Rembrandt van Rijn

Now, another favorite and significant inspiration of mine: the world of Rembrandt van Rijn, a masterful artist who wove chiaroscuro and psychological depth into his works. In The Night Watch, Rembrandt’s mastery of light and shadow is almost palpable, creating a portrayal of the human form that transcends mere nudity. Within the dynamic militia scene, the interplay of light and shadow subtly highlights body contours and armor, breathing life into each figure. Rembrandt’s meticulous attention to detail imbues his subjects with a profound sense of humanity, while the symbolism of the militia company conveys strength and civic pride. Through this intricate interplay, Rembrandt integrates the human body into the fabric of the painting, showcasing his lasting influence on the depiction of the “nude” form as both a vehicle for realism and a conduit for symbolism during the Dutch Golden Age.

As we inspect The Night Watch, we encounter arguments that invite reflection. Some might assert that the painting earned its status as a masterpiece by adhering to the artistic traditions of the Dutch Golden Age, particularly its innovative use of light and shadow to depict form and texture. This celebrated chiaroscuro undoubtedly influenced future approaches to the human form in art. However, such reasoning assumes the effectiveness of this portrayal without directly addressing whether The Night Watch truly emphasizes the nude form at all.

As we delve into The Night Watch and its depiction of the human form, it’s essential to remember that art is a dialogue between the canvas and the observer. Your perspective adds depth to this narrative. So take a moment to reflect: What resonates with you? Your interpretation is an invaluable part of the ongoing conversation about this masterpiece.

Reference to Francis Bacon

For Francis Bacon, an artists that was a gateway to the profound complexities of existence, a creative influence for exploring vulnerability and imperfections. Bacon’s fascination with the human form transcends the superficial. He saw the artist as a truth-seeker, tasked with capturing the very essence of their subject, even if it meant delving into raw and discomforting portrayals.

Bacon’s artistic philosophy stands in direct challenge to prevailing fallacies. He bravely questioned established norms of beauty and idealization, often portraying the human body in ways that defy convention. Take, for instance, his work “Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X” (1953). Here, Bacon depicts the Pope’s figure in a contorted, grotesque fashion, dismantling traditional notions of portraiture. In doing so, he confronts the fallacy of appealing to tradition by exposing the limitation of traditional representation. Where tradition might argue for the inherent beauty and universality of classical nudes, Bacon’s work argues for a broader, more inclusive interpretation, one that prioritizes emotional truth over visual harmony.

In challenging the appeal to tradition, Bacon’s art provokes us to question why certain representations of the human form are deemed authentic or beautiful. His distorted nudes remind us that art evolves alongside societal perceptions of beauty, vulnerability, and truth. By breaking with tradition, Bacon invites a deeper interrogation of how and why certain ideals endure – and whether they should.

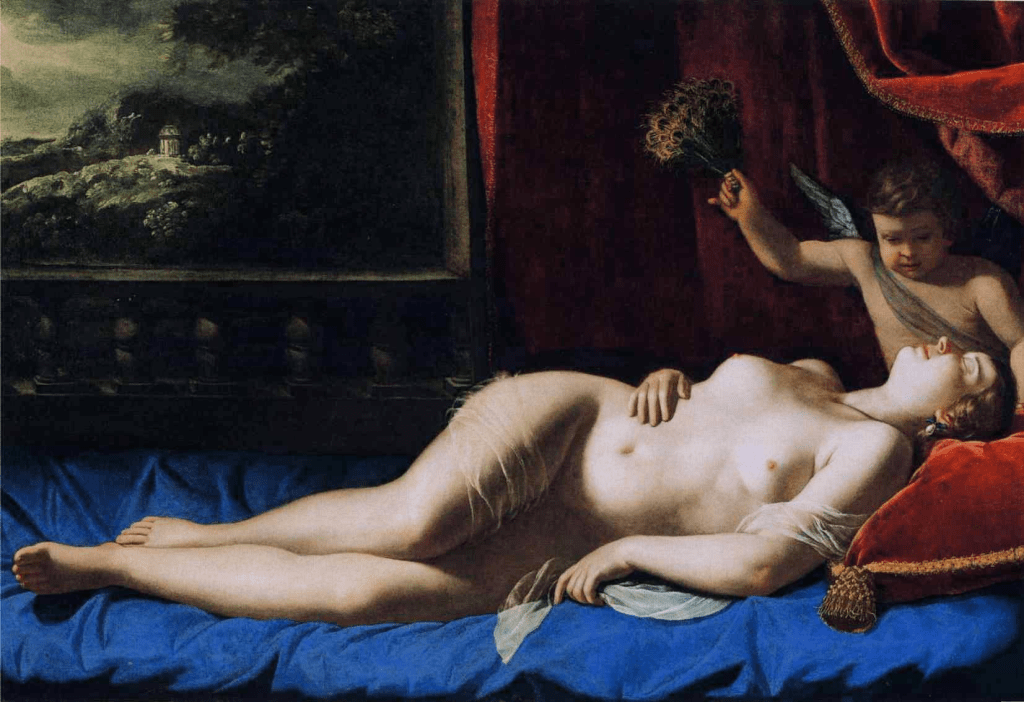

Reference to Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi, a true pioneer of her era, carved her mark as an artist known for the powerful, emotive narratives that graced her canvases, often portraying heroic women from history and mythology. While her focus predominantly revolved around historical and biblical tales, she ventured into the realm of nudes within these contexts. One standout piece, “Judith Slaying Holofernes,” exemplifies her mastery in depicting the human form and her unmatched ability to evoke intense emotions through her art.

In contemplating Artemisia Gentileschi’s nudes, we are confronted with a pivotal question: What defines the authenticity of her portrayal and the underlying intent of her work? Gentileschi’s dedication to portraying strong, dynamic women challenges the conventional representation of women in art, casting them not as passive subjects, but as active agents in their own narratives. Her paintings transcend mere aesthetic allure, delving into the intricate realm of human emotions, agency, and vulnerability.

Still, as we examine this facet of Gentileschi’s artistry, we are reminded that her work is more than just a disruption of societal norms. It invites us to witness the profound humanity in her subjects, their strength, their pain, their resilience. The artistic merit of her nudes lies not only in their defiance of tradition but in their ability to evoke a deeply personal connection with the viewer. Through her brushstrokes, Gentileschi portrays the nude form with authenticity, bridging the gap between history and the timeless truths of the human experience.

Rethinking Tradition and Authenticity

As we explore the diverse perspectives of artists like Egon Schiele, Rembrandt van Rijn, Francis Bacon, and Artemisia Gentileschi on the human form, we encounter a dynamic dialogue challenging established norms.

Francis Bacon embraces vulnerability and imperfection in his paintings to disrupt tradition. Similarly, Schiele uses decorative eroticism and figurative distortions to aggressively subvert the conventional, pushing the boundaries of artistic expression in his era. Artemisia Gentileschi’s defiance of early societal expectations invites us to critically examine the inherent value of her depictions of nude women. Across this array of artistic discourse, the ideals of beauty shift and transform. Each artist not only redefines the human form but also shapes the ongoing conversation about representation and authenticity. Through their work, we are reminded that art continually evolves, not just with techniques, but in its power to challenge our perceptions and question established norms.

In exploring the fallacies of Begging the Question and Appeal to Tradition, a broader understanding of authentic nudes begins to emerge. Part 1 highlighted how assumptions about authenticity often reinforce circular arguments—where the value of the nude is asserted without proving why it should hold inherent artistic merit. In Part 2, we delved into how traditional ideals of beauty and form constrain our perceptions of nudes, with figures like Francis Bacon and Artemisia Gentileschi offering vital counterpoints that challenge the status quo.

Together, these fallacies expose a tension at the heart of the discourse: the struggle to define authenticity without succumbing to either unexamined traditions or self-reinforcing claims. This tension compels us to question not only the purpose of the nude but also its implications in a modern context. If authenticity lies beyond tradition and unfounded assumptions, what happens when the nude is stripped of its artistic pretense altogether?

This leads us to the next chapter of the discussion: From Artistic Expression to Objectification. Here, we will navigate the precarious line between celebrating the human form and reducing it to a mere object, exploring how societal shifts and artistic intent redefine the role of the nude in contemporary culture. As we proceed, the question evolves: Can the nude maintain its artistic integrity in a world increasingly concerned with power, gaze, and representation?

Leave a comment